Stories they bring to class: Broken homes, lost jobs, troubled lives

Harish’s father is a daily-wage worker who says he needs to take his wife once a month to a dargah to treat her “mental illness”. When they are out, no one’s there to ensure Harish goes to school. Siddharth’s father is an alcoholic and his mother, who recently lost her anganwadi job, says he often turns violent and beats her up. Keerti’s father, a fruit seller, struggled through the pandemic to buy his three children a phone to help them through their online classes.

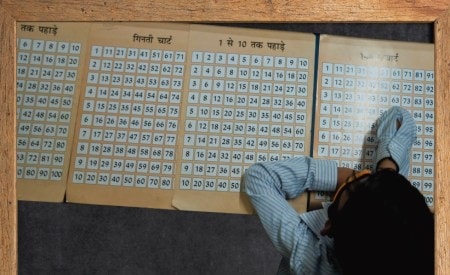

The vulnerabilities of these families frame the multiple back stories that make Neha Sharma’s task — as mathematics teacher of Class 5A of the Delhi government’s Veer Savarkar Sarvodaya Kanya Vidyalaya — one of the most challenging as she attempts to bridge the learning gap after two years of an unprecedented pandemic-induced shutdown.

In fact, each of Neha’s 38 students, including 10-year-olds Harish, Siddharth and Keerti bring to the classroom a unique set of challenges encumbered by their personal stories.

Tracking Class 5A through five weeks — sitting in for each of their 26 math classes — The Indian Express found that as the children navigated coursework in the classroom, the challenges outside were equally daunting. Especially when the pandemic has been particularly harsh on children from economically weaker sections and working-class families, the demographic that constitutes much of Class 5A.

In a basic assessment conducted mid-March, days before schools reopened in Delhi on April 1, Neha had marked some of the children as needing special attention. Harish had failed to do two-digit subtraction and identify single digits – he was a ‘beginner’. Siddharth had, with a little coaxing, identified two-digit numbers, but failed to do division or subtraction – he was behind a lot of children in class. Keerti, like most others in her class, couldn’t do division with remainders.

So on April 2, the first parent-teacher meeting (PTM) of the academic session, Neha is determined to meet their parents and talk about the “extra push” the children will need to get them ready for Class 5.

“Vacation mein kahin mat jaana (Don’t go anywhere during the vacations). There will be special classes,” Neha tells each of the parents during the PTM.

As schools reopened, to full capacity, on April 1, the Delhi government had decided that until mid-June, classes 3 to 9 would set aside the syllabus and focus on the basics of reading, writing and maths.

Around noon, close to the end of the session, Siddharth’s mother arrives and sits across the table from Neha. Neha notices the angry scar on her left forearm, long healed but ridged with prominent stitch marks. “Siddharth’s father often gets drunk and beats me in front of the children. Our home is no place for children to study,” says the 41-year-old. Neha asks if she can speak to Siddharth’s father, but his mother is afraid: he might end up hitting Siddharth if he gets to know the boy doesn’t do well in school.

Neha tells The Indian Express, “It’s very important for us to know the family background of the children. That helps me get a sense of what I need to do to address the child’s specific needs.”

Throughout the PTM, Neha takes turns to be teacher, counsellor, friend — encouraging at times, gently chiding at other times, laughing along with some parents and listening intently to their personal stories.

She tells Vismaya’s mother that the child is pareshan (troubled); shares diet tips with other parents — “try grating vegetables into cheela and paratha, make sambhar and mash vegetables into it” — and tells Dipesh’s elder brother, who has turned up with an aunt on behalf of his parents, that he is responsible for ensuring his brother’s homework is done.

Days later, at Siddharth’s home in a southeast Delhi neighbourhood, his mother says the 10-year-old cries on days that he can’t go to school. Earlier that week, she recalls, her husband got into a drunken fit, and she couldn’t send Siddharth to school on time. “So I made him miss school that day. He was very upset,” she says.

Her husband has not worked since Siddharth was a baby while she lost her job as an anganwadi helper after the recent protests by anganwadi workers in the Capital. Their eldest daughter, 19, now works as an anganwadi helper for Rs 5,610 a month and is the only earning member in the family of six. Siddharth’s two other sisters — one in Class 10 and another in Class 7 — are in the same school as him.

For more than two years, the boy who “loves school” found himself confined to his difficult home.

“It has always been difficult to study at home,” says Siddharth’s sister, who is in Class 10. Our father gets drunk, does maar-peet (gets into fights). The three of us sit together in the evenings and do our homework and study. It’s hard to focus… I know Siddharth can’t remember things because of all this.”

During the pandemic, the three school-going children and their father shared a smartphone, but even the phone was not spared — Siddharth’s father broke it twice in his drunken fits of rage, says his mother.

“Siddharth often missed his worksheets and online class work during the pandemic because he couldn’t get the phone. I am glad he is back in school. He looks happier now. I want to find him some tuition class but we can’t afford it right now,” says his mother.

In most cases, paid tuitions filled a key gap while schools shut during the pandemic. The Annual Survey of Education Report (ASER) for 2021 had found that students from poor families depended more on private tuitions during the pandemic years than earlier — while 28.6% of school-going children attended private tuitions in 2018, this up to 32.5% in 2020 and 39.2% in 2021.

Yet, in some ways, it only served to create another layer of inequity within classrooms like Neha’s. While many such as Siddharth’s mother struggled to pay for tuitions, parents of Janani, whom Neha counts among her “bright” students, pay Rs 900 a month for the private classes.

“Tuition ma’am paise toh zyaada leti hai (charges a lot). But we have to think of our children’s future, we want them to grow up to become something,” says Janani’s mother, a homemaker who has studied till Class 10.

The pandemic years also served to highlight another established link: between parents’ education and classroom performances of children. For instance, Salik, one of Neha’s students with a quick grasp of math concepts, was taught over the last two years by his accountant father, a B.Com. (Honours) graduate.

On May 6, Neha finally gets to meet Harish’s father for the first time — she had made repeated attempts to get through to him on the phone and sent word through the van driver who drops children off at school.

A daily-wage worker, he says he was away in Rajasthan — a monthly trip he makes with his wife to a dargah there to treat the “mental illness” that has troubled her for years.

Neha points out that in April, Harish was present in class for 13 days and absent for 10. His father replies that when he is not around, there’s nobody to ensure that he actually goes to school.

Flustered and disoriented as he speaks — “dimaag theek se nahi chal raha because of all this tension” — he says he got no work during the pandemic. “Those years destroyed me completely. There were times when there was no money to buy food. My father also got COVID,” he says.

He lost his phone during the pandemic and so Harish had no access to the worksheets and assignments that the school sent through WhatsApp.

Now in school, Harish is still unable to do things that children usually learn in preschool. Even after five weeks of Neha’s intense catch-up sessions, Harish still couldn’t identify numbers from 1 to 9.

“I know he’s the weakest student in the class. I want to give a little more attention to his studies. I’m trying to get him enrolled in a tuition class but they have been asking for an advance payment. Let’s see,” he says.

Neha knows that only means she will have to try that much harder.

“The children who are struggling in class evidently don’t have the right family environment. So I will have to work on them a little more. I think Siddharth is responding well to the extra attention, but I have to work harder with Vismaya and Harish,” says Neha.

(Names of children have been changed to protect identities)